Hypothesizing Reciprocal Altruism Therapy For Cats

by Steven Gussman

THE PROBLEM

My sister, Katie Gussman, and her boyfriend, J. C. Lopez have two pet cats, Twitchy and Chewy.1 These cats grew up together in their home(s) from a relatively young age (though old enough to be spayed and put up for adoption, at a few months), and generally got along. Presently, they must be kept on completely separate floors of their home so that Chewy does not violently attack Twitchy (ironically, Katie identifies Twitchy as having been the benevolent dominant before this began). Even from separate floors, Chewy will howl at and track Twitchy. Between the two of them, several hypotheses have been proffered about what caused this. J.C. thinks it has something to do with an event that occurred just weeks before the problem began: Katie brought the cats to our parents' home, which houses two cats, Catnis and Datchi (a generally non-violent, rescued stray). Upon introduction, Chewy and Datchi immediately began a violent bout (in which I believe Datchi was the aggressor). I am sympathetic to this explanation as animals of the same sex have dominance hierarchies associated with mate (and other resource) access, and fighting is one way that a dominant-subordinate relationship is established; it's possible that for whatever reason that Datchi attacked Chewy (gravely scaring Twitchy in the process), this changed Chewy and Twitchy's relationship by changing their position(s) in a dominance hierarchy.2 Another possible causal factor is that Chewy suffers from an irritated skin condition which causes her to scratch and bite patches of her fur off in an effort to attenuate the discomfort; Katie and J.C. posit that perhaps the overall irritance causes her to be more aggressive.3 Though Chewy's not great at keeping her medicine down (nor are we great at making sure she gets her regular doses), medication did not seem to change her relationship with Twitchy even as it seemed to reduce her bald-spots.

The kinds of remedies readily on offer tend to by highly simplistic, naive, and (at least in this case) seemingly ineffective. For example, one recommendation Katie and J.C. tried was to feed the cats treats while they were near each other in the hopes of triggering brute behaviorist conditioning: either they'll associate being near each other with the good feelings of getting treats, or by breaking bread with each other, they will form a friendship bond (though I think this gets the causality backwards). Very slight, temporary success seemed to be had with this before the problem began again. There are plans to bring the cats to an alleged expert in such matters, but I suspect the kinds of prescriptions involved will be similarly innocent of the underlying biology, expensive, and ineffective.

EVOLUTIONARY THEORY

In 1859, Charles

Darwin published his (and Alfred Russel Wallace's) theory of

evolution by natural

selection.4 This elegant theory explains the mechanism which generates

biodiversity: given some starting point of a replicator (perhaps a

self-replicating molecule, the simplest “metabolism” which takes

energy from its environment and creates copies of itself), the

realization is that these copies will not be perfect, meaning some

will contain mutations, most

of which will be bad but some of which will increase replication and

therefore breed true (have more children), showing up in higher

frequencies in the future.5 Those selected-for traits (or phenotype)

which the mutation in the genes coded for are called adaptive

(because they are suited for increasing replication in the

environment in which they evolved). For example, the eye is adapted

to detect light because an information-rich bath of it existed in the

environment in which it was selected (information which helped the

organism survive and reproduce). Darwin and Wallace added to their

theory that in sexual organisms, certain mate-choice strategies (or

attractions) will be naturally selected for, and the breeding-effect

of these (mostly female) mate-choices on the phenotype

of their mates' sex (mostly males) is called sexual

selection.6 For example, the colorful displays common in male (but not female)

birds are due to the greater female choosiness in mates (particularly

showy mates).7 The flip-side of this coin, intrasexual competition,

is the tendency for same-sex

competition for access to opposite-sex mates of the highest quality.8 Around 1964, W. D. Hamilton, J. B. S. Haldane, and R. A. Fisher

introduced kin selection:

the theory that altruistic behavior towards kin is naturally selected

for proportional to the individual's relatedness (one helps their

sibling because on average, they share half of one's genes, and so

each time a sibling reproduces, it is as though one has

half-reproduced in terms of the passing on of one's genes—the

ultimate purpose of organisms or gene-vehicles).9 In the 1960s and 1970s, William Hamilton, George Williams, and

Robert Trivers introduced reciprocal altruism:

the theory of why non-kin behave altruistically towards each other:

because there are situations in which trade leaves both parties with

higher fitness than they began with.10

Biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky wrote: “nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”11 Every life-science (biological, psychological, sociological, economic, or political) phenomena requires both a proximal explanation (a description of the event as it plays out in the present) and ultimate (adaptationist) explanation for why the trait was selected for in pre-history.12 Darwin anticipated the vast domain of his theory well ahead of time, himself applying it to psychology.13 In 1987, psychologists Leda Cosmides and John Tooby founded the field of evolutionary psychology in earnest, as they recognized that The Standard Model Of Social Science tended to focus merely on proximal labeling, description, and explanations of social phenomena.14 A bit earlier than that, entomologist E. O. Wilson founded the similar field of sociobiology, the application of evolution to sociology. Ever since, one promising road towards progress in the social sciences has been to identify a field which is innocent of evolutionary theory, and apply it to make new discoveries in those domains. In the 1990s, George Williams and Randolph Nesse founded the field of evolutionary medicine (which pays special attention to our immune responses as adaptations, and which may see certain phenotype traditionally attributed to the host as the extended phenotype of the disease's genes, forwarding its own genetic goals);15 more recently, Nesse again founded evolutionary psychiatry (which is a mix of evolutionary psychology and evolutionary medicine);16 and Gad Saad has helped introduce the field of evolutionary behavioral economics.17 I would like to introduce evolutionary pet behavioral therapy.

Despite having been relatively young kittens, Chewy and Twitchy may have nevertheless been too old to trigger strong bonds via kin selection mechanisms; whatever the cause, this is evidently not in play and is impossible to trigger late in life.18 This leaves reciprocal altruism, the ultimate basis for friendship across the animal kingdom. Regardless of the cause of the cats' quarrel, the goal is to induce behavior which will change the cats' relationship from one of zero-sum competition, to one in which the cats increase each others' genetic fitness. Inducing reciprocal altruism is not expected to be trivially easy to do, but it does provide a deep framework for the kinds of therapies that may promote robust pro-social behavior between two members of the same species. The idea that originally came to mind was the following experiment.

THE EXPERIMENT

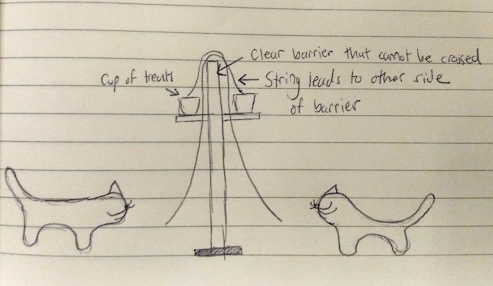

I imagine placing a tall, clear barrier between the two pets such that the subordinate is safe from any physical attacks by the aggressor, but such that they can still see and come close to each other. Each side will have an out-of-reach shelf holding a cup of cat food with a string attached to it and hanging down the opposite side such that when each cat plays with their string, it knocks the food down on the other cat's side. This process would be repeated once a day for a period of time before attempting to re-introduce the cats to see if it had an effect on their relationship (likely followed by more therapy even if the initial meeting goes well).

The hope is that this will trigger reciprocal altruism modules by the cats recognizing that they are cooperating to feed each other. While this may work best in terms of triggering reciprocal altruism when the cats are hungry, I would not want to risk this hunger exacerbating the aggressor; treats will be used instead of meal-food. Much could go wrong! Behavior such as hissing from the aggressor may make the weaker cat run away from the apparatus. It may be that the cats cannot recognize that they are feeding each other (their actions feeding the other may even upset them, further). It may be that the reciprocal altruism module for recognizing cooperative-feeding is too specific and the cats' minds cannot generalize from this contrived apparatus that they are feeding each other in the reciprocal altruism sense.18 It may be that cats never fed each other in pre-history and so no such cooperative feeding basis for reciprocal altruism exists in house cats! (I am doubtful of this, however, hypothesizing instead that humans did not artificially select the cats-bringing-hunted-presents behavior whole-cloth during the domestication process, but instead as an exaptation on an old adaptation in which cats fed each other in this way).19

NEXT STEPS

As this is a sensitive situation (I do not want to cause further problems with these cats!), I have acquired two books I would like to read prior to conducting experiments to build a working knowledge of cats and their social lives: The Tribe Of Tiger: Cats And Their Culture by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas (Simon & Schuster) (1994) and Catwatching: Why Cats Purr And Other Feline Mysteries Explained by Desmond Morris (Crown Publishers) (1986). This knowledge may convince me that my original idea is bad and / or that a new reciprocal altruism mechanism would be better exploited for this purpose, or otherwise include that cats did feed each other in pre-history, supporting an attempt at the above experiment. From there, an actual case-study experiment must be conducted on Chewy and Twitchy, and a paper written on its results. If evolutionary pet behavioral therapy is viable, it would have further applications such as for treating animal relationships in zoos, as well as for expanding potential experimental designs in zoology.

FOOTNOTES

1. Katie and J.C. are not involved with this paper and their endorsement of anything I say should not be implied by their mention.

2. For the example of lobsters, see 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote To Chaos by Jordan B. Peterson (Random House Canada) (2018) (pp. 1-30).

3. My original response was to wonder if some kind of “you hurt me” mechanism was being triggered when Chewy felt irritated skin with Twitchy nearby, as if she confused her skin condition for an injury caused by Twitchy in those moments (though I highly doubt this).

4. See The Selfish Gene by Richard Dawkins (Oxford University Press) (1976 / 2016) (pp. 1, 359) which quotes zoologist G. G. Simpson, “Charles Darwin: British Naturalist” by Adrian J. Desmond (Encyclopedia Britannica) (1999 / 2021) (though I have not read this full entry), and The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial Of Human Nature by Steven Pinker (Penguin Books) (2002 / 2016) (pp. 530).

5. See The Selfish Gene (pp. 18-23).

6. See The Selfish Gene (at least pp. 204-206) and The Ape That Understood The Universe: How The Mind And Culture Evolved by Steve Stewart-Williams (Cambridge University Press) (2018) (at least pp. 20-23, 43-45, 68).

7. See The Ape That Understood The Universe (pp. 68).

8. See The Selfish Gene (at least pp. 204-206), The Blank Slate (pp. 252, 319, 346-347, 407-408, 471) which further cites at least “Blum, 1997; Buss, 1994; Geary, 1998; Ridley, 1993; Symons, 1979” (though I have not read all of these works), and The Ape That Understood The Universe (at lease pp. 22-23, 67-68).

9. See The Selfish Gene (generally pp. 116-140), The Blank Slate (at least 245-247), The Ape That Understood The Universe (pp. 24-27, 177-192, 308) which further cites at least “Hamilton (1964)” (although I have not yet read this work), and Consilience: The Unity Of Knowledge by Edward O. Wilson (Vintage Books) (1998) (pp. 183. 340) which further cites Sociobiology: The New Synthesis by Edward O. Wilson (Harvard University Press) (1975) (though I have yet to read this work).

10. See The Selfish Gene (generally pp. 216-244), The Blank Slate (generally pp. 244-268, 471) which further cities at least “Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971; Trivers, 1972; Trivers, 1974; Williams, 1966” (though I have not yet read these source works), and The Ape That Understood The Universe (generally pp. 193-202, 318) which further cites at least “Trivers (1971)”.

11. See PBS' entry for “Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution” (https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/evolution/library/10/2/l_102_01.html). (I could have sworn this popular quote would turn up in one of my evolution books on hand, but after due diligence, it has not).

12. See “THE SAAD TRUTH_2: Key Tenets of Evolutionary Psychology” (Gad Saad) (2014) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K_ytuWSnc9I) (2:55-6:04).

13. See “Evolutionary Psychology: A Primer” by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby (Center For Evolutionary Psychology) (1997) (https://www.cep.ucsb.edu/primer.html) (though I am not sure that I have read this entire work) and How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker (W. W. Norton & Company) (1997) (though I have not yet finished reading this work). [Author's note: I do not have easy access to my copy of Pinker's book at my sister's home in the PA mountains at the moment, so I plan on refining this citation upon returning to NJ].

14. See “Evolutionary Psychology: A Primer” which further cites “From Evolution To Behavior: Evolutionary Psychology As The Missing Link” by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby (MIT Press) (1987) (though I have not yet read this work).

15. See The Extended Phenotype: The Long Reach Of The Gene by Richard Dawkins (Oxford University Press) (1982 / 1999) (especially pp. 318-380), Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine by Randolph M. Nesse and George C. Williams (Vintage Books) (1995) (though I have yet to read this work), and “My Chat with Evolutionary Medicine Pioneer Randy Nesse (THE SAAD TRUTH_101)” (Gad Saad) (2015) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VokpuzXtqXs).

16. See Good Reasons for Bad Feelings: Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry by Randolph M. Nesse (Dutton) (2019) (though I have yet to read this work).

17. See “THE SAAD TRUTH_3: Roots of My Evolutionary Consumption Journey” (Gad Saad) (2014) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_O_jjJdNN8o).

18. See The Selfish Gene (generally pp. 114-140), The Ape That Understood The Universe (pp. 132-133, 185-186, 189), Consilience (generally pp. 163-199), and “Michael Shermer with Dr. Debra Lieberman — Objection: Disgust, Morality and the Law” (Skeptic) (2018) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tyBksb89d70) (17:39-30:02).

19. An exaptation is when an old trait is first useful in a new way (and can than be selected for and modified by that new pressure), see “Exaptation” by W. Tecumseh Fitch's in This Idea Is Brilliant: Lost, Overlooked, and Underappreciated Scientific Concepts Everyone Should Know edited by John Brockman (Harper Perennial) (2018) (pp. 11-13).

Change Log:

ReplyDeleteVersion 0.01 6/10/21 8:35 PM

- Fixed the "20" superscript to no longer be italics (for final footnote)

Version 0.02 6/10/21 8:36 PM

Delete- Added a tag for "evolutionary pet behavioral therapy"

Version 0.03 6/10/21 9:34 PM

Delete- Removed the following final sentences from the first "EVOLUTIONARY THEORY" paragraph:

"For example, when certain primates pick insects off of each other. Hamilton's and Trivers' reciprocal altruism inequality for whether a trait will be selected is:

br > c

where b is the recipient's benefit, r is the percent-relatedness variable between the recipient and altruist, and c is the altruist's cost.[11]"

and the related 11th footnote (shifting footnotes 12-20 to now be 11-19):

"11. See The Blank Slate (pp. 244, 471) which further cites 'Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971; Trivers, 1972; Trivers, 1974; Williams, 1966' and The Ape That Understood The Universe (pp. 183)."

because I realized that I had displayed the kin selection inequality as though it were a reciprocal altruism inequality (kin selection is not the topic of this paper).