The Passive Smell Hypothesis

by Steven Gussman

THE HYPOTHESIS1

Why do warm things smell more-so than cold things? The obvious answer is that temperature is just the average kinetic energy of the molecules in a substance: colder things are stiller, and the constituents of hotter things are more-so in motion. This motion should then kick off molecules into the environment where they may be received by noses: smelled. Yet this explanation is purely physical, what if there is another cause, shaped by evolution by natural selection? Perhaps the effect is also by virtue of the fact that by being warm, the scent preferentially travels towards cool noses.

The passive smell hypothesis is that in animals for which smelling is an important sense (for sensing one's inert environment, and for communication via pheromones), the nose is elongated away from the warm body; made of cartilage; moist or runny (especially in colder weather);2 has poor circulation; all to ensure that it is cooler than the environment (particularly the molecules to be detected) so that (relatively warmer) scents will move towards the (relatively cooler) nostrils by the second law of thermodynamics.

This hypothesis predicts no-or-flat noses in the seas as with fish and turtles, and largely even amphibious frogs (whom presumably use their nostrils to breath with their mouths shut more-so than to smell). On the other hand, bottle-nosed dolphins and porpoises have prominent snouts (though they are accompanies by an elongated jaw, and these creatures have a relatively recent pre-history as land mammals). Conversely, the hypothesis predicts that hotter areas will have longer-noses with smellier environments (whereas cooler places such as the poles and high altitude mountaintops will have shorter noses with fewer scents). The animals most associated with the sense of smell have exactly the expected characteristics: dogs and pigs, for example. These creatures have long, protruding snouts with special, non-furred noses at the end which remain very moist (and as a result of all of this, cool to the touch).

It seems as though we only ever actively sniff (most often to confirm something we, “got a whiff of,” passively) to catch a conscious scent, as from food, to adjudicate its quality (evolutionary biologist Bret Weinstein and I have both independently predicted that the evolutionary logic is such that smells are “bad” as a warning not to eat, and to function, the scent cannot make you sick).3 Yet we do not have much, if any, intuitive sense that we are experiencing pheromones (much as we have little intuition over our internal world of hormonal causes): perhaps passive smell of the kind I'm talking about will also then be more-so present in social animals. Indeed, dogs and wolfs, with their prominent and specialized noses, come in packs. Cats rely on smell quite a bit but are both less social and less extremely nose-specialized, phenotypically.

THE EXPERIMENT

Everyone knows that heating a substance will make it smell, and perhaps most are apt to accept that it is only because more molecules are being kicked off due to the higher average kinetic energy. But some experimental designs should be capable of teasing apart the difference in causation. Namely, the controlled experiment in which one group's noses are left normal, one has their noses cooled (perhaps with ice), and another has their noses warmed; and each is placed in the presence of the same source of scent (of the same temperature) and asked what they smell with a blind-fold on, and the magnitude of the smell on a scale of one-to-ten.

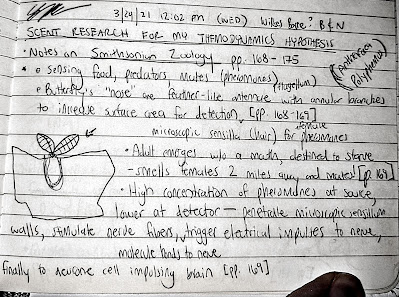

SELECTED JOURNAL PAGES4

Footnotes:

1. I had this ideas around Christmas-time 2020, and continued to flesh it out into early 2021.

2. Keep in mind that we perspire because this water cools our bodies when over-heating.

3. Weinstein made this comment on an episode of The DarkHorse Podcast.

4. Mentioned in these journal notes is Zoology: Inside the Secret World of Animals (DK) (2019) (pp. 168-175), which I looked over at a Barnes And Noble in late March 2021.

Change Log:

ReplyDeleteVersion 1.01 2/5/23 7:55 PM

- Fixed the tags to be separated by commas, not semi-colons